In the late 50s, French critics who wrote for the film journal Cahiers du Cinema began to make films of their own, using a new language that was both fresh and nostalgic in its presentation. The five directors most associated with the French new wave were Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette, though each brought a unique vision that was entirely his own. Both Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) and Godard’s Breathless (1960) are often cited as the two films that define the genre. The new wave movement (according to Bordwell and Thompson) lasted from 1959 to 1964, yet this is conservatively speaking, for aesthetically the new wave can be seen continuing up until Rivette’s Out One (1971) or Jean Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore (1973). Yet one film in particular that positions itself somewhere between new wave and post-new wave is Truffaut’s Stolen Kisses (aka: Baisers Voles) (1968). Truffaut’s third sequel of his first film The 400 Blows follows his autobiographical character Antoine Doinel (new wave actor Jean-Pierre Leaud) to a later stage of his life. Though the new wave style is often linked with Godard’ jump-cuts or Truffaut’s early cinema verite technique, all the directors associated with the new wave had tremendous affection for Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray and French directors Jean Vigo, Jean Renoir, and Jacques Tati. Although it is not explicitly obvious, Stolen Kisses continues the new wave tradition of these influences as well as establishing a form with which Truffaut would be later associated.

Stolen Kisses opens with a dedication to Henri Langlois who was head of the Cinematheque until his replacement by Pierre Barbin (which happened only four days into the shooting of the film). The opening shot of the closed Cinematheque and the dedication informs the audience of the film’s reflective and self-conscious nature. If the French new wave’s goal was to present an awareness of the process of filmmaking, then Stolen Kisses continues this trend with numerous examples. The firing of Henri Langlois can be seen as a parallel to protagonist Antoine Doinel’s dismissal from the military for misconduct. As Antoine is being un-honorably discharged, he mocks the military’s accusations that he was unfit for service (he had continually gone AWOL to pursue romantic interests). Yet these claims from the military are substantiated, for Antoine immediately visits a brothel after his release. Antoine is not merely an autobiographical character derived from the youth of the director (who was also discharged under the care of mentor Andre Bazin), but also a representation of the director’s current interests. Antoine will later be found reading the book of Truffaut’s next film Mississippi Mermaid (1969) as well as courting Christine Darbon (who was played by Truffaut’s current fiance Claude Jade). However, it must be noted that Antoine Doinel is a character who is fixated on the past, lacking interest in the modernization of France. As student and labor unrest was building to the Parisian riots of May 1968, Antoine seems unconcerned with such political agendas and is more focused on his romantic entanglements.

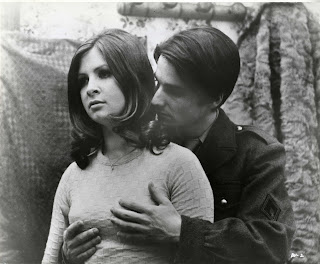

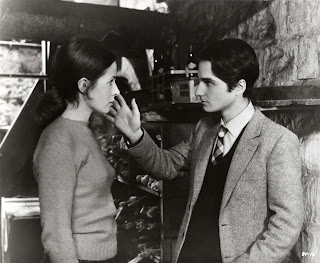

One of Truffaut’s reoccurring cinematic obsessions is presenting characters that suffer through romantic “love triangles.” As seen in some of his earlier films like Jules and Jim (1962), Love at Twenty (1962), The Soft Skin (1964), and Fahrenheit 451 (1966), Truffaut meditates on the frustrations of love on unequal terms. The director as auteur theory is substantiated throughout Stolen Kisses, with Antoine being emotionally torn between his young love Christine (Claude Jade) and the older Fabienne Tabard (Delphine Seyrig). This instability of triangular love manifests into Antoine’s manic recital of identity in the mirror. As he continuously verbalizes the names of the two girls he loves, he also incorporates his own name as a form of identity placement between the two women. Through this continuous enunciation, he is driven to a moment of madness from which he eventually releases himself. Throughout the film, almost all of the characters suffer as the ones they love always seem to have stronger feelings for someone else. If the French new wave critics had coined the term auteur theory, then the directors involved made sure to reinforce this with their continual output of like-minded themes. Truffaut would continue this obsession in his following films Bed and Board (1970). Two English Girls (1971), Such A Gorgeous Kid Like Me (1972), Day For Night (1973), The Story of Adele H (1975), Love On The Run (1979), and The Woman Next Door (1981).

In Godard’s Breathless, the director takes influence from earlier film noir or crime films from the 40s and 50s and reinvents the genre with a kinetic pace or a “fly on the wall” perspective. Instead of using high-contrasting shadows, Godard utilizes existing natural light giving the film a more realistic tone. In Stolen Kisses, Truffaut takes the job of a private investigator (which is typically associated with film noir) and injects it into the framework of a romantic comedy. If the earlier new wave films were closely reminiscent of film noir due to the dark cinematic themes or the black and white photography, then Stolen Kisses offers a post-new wave Eastman color and a lighter thematic tone. The Paris that is depicted in Stolen Kisses is seemingly more tranquil than the actual events happening at the time, which gives the film a locked or focused perspective of the protagonist. In one humorous scene of the film, Antoine talks to Christine on the phone and is shocked to hear that she was at a student protest. It is ironic that Antoine may not have known anything about the heightened political climate, for he is so consumed by love. Unlike Godard (who relished political grand standing), Truffaut takes every opportunity to downplay a political angle.

Stolen Kisses is often ignored in the context of the new wave, and this is somewhat of a disservice to a film that experiments with various French cinematic styles. When Antoine is being hired as a private investigator, he is told that “ten percent [of the job] is inspiration and ninety percent is perspiration.” These words are borrowed from one of Truffaut’s heroes, Jean Renoir, who used the very same line in the film The Crime of Monsieur Lange (1936). Truffaut also uses Renoir’s cinematic technique when panning across rooms, delivering information about an event or character through shots of miscellaneous items. Another icon that Truffaut cinematically mentions is Jacques Tati, with an obvious look-alike, performing a comical routine with an umbrella and train door. These humorous moments present a nostalgic director, who succumbs to using a sentimental song by Charles Trenet (where the film gains its title) to punctuate the poetry of the narrative. Truffaut experiments with documentary-style filmmaking as well, when presenting Antoine’s love declaration, which travels through the Paris postal service. Short as the scene may be, it reminds one of Alain Resnais’ early documentaries, as the viewer watches Antoine’s letter travel through the many different districts to finally arrive at the home of Fabienne Tabard.

When Truffaut made Stolen Kisses, the French new wave was already influencing new American directors who were beginning to produce their own brand of new wave films. From John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959) and Faces (1968) to Arthur Penn’s Mickey One (1965) and Bonnie and Clyde (1967), American films were beginning to show the impact of French cinema. Yet, with Stolen Kisses, Truffaut seems to be channeling the spirit of the disenfranchised younger generation that was made so popular in The Graduate (1967), a similar film of a meandering youth caught in a love triangle with a younger and older woman. Though Stolen Kisses has quintessential new wave applications, its overall product must be seen as post-new wave in form. Right before the film was being made, Truffaut had spent extensive time working on a Bonnie and Clyde script (a film he was close to directing) and finishing up his interviews for his famous Alfred Hitchcock book. Through the process of interview, there seems to be an exchange of ideas between French and U.S. cinema in 1968. For not only is Truffaut adopting new American cinematic concepts, but director Hitchcock would also use Truffaut’s actress Claude Jade in his next film Topaz (1969). The autobiographical character Antoine Doinel would also influence director Brian DePalma, with his protagonist Jon Rubin (Robert DeNiro) of his early films Greetings (1968) and Hi Mom! (1970). Both characters Antoine Doinel and Jon Rubin are emblematic of both directors’ obsessions, whether it is love or voyeurism.

Truffaut would follow-up the adolescent exploits of Antoine Doinel in his next two installments: Bed and Board (1970) and Love On The Run (1979). Bed and Board would draw more influence from Stolen Kisses than any other film outside the new wave; though highly enjoyable, the film often feels like a collection of recycled vignettes that had already been presented. Love on the Run would become a pastiche of the Doinel series, which spends far too much of its running time using old footage from all four films. Stolen Kisses acts as a turning point between the new wave and post-new wave, utilizing both past French cinematic expression and the American cinema that it influenced. If Truffaut was channeling such traditional directors as Jean Renoir, Jacques Tati and Alain Resnais, he was also expressing the spirit of new American directors, like Mike Nichols and Arthur Penn. Breaking new wave tradition, Truffaut created a unique film about youth that fits comfortably between foreign art-house and popular cinema.

Stolen Kisses (for me) has got to be one the most beautiful film ever made. All of the films in the Antoine Doinel cycle are brilliant (even the half-baked "Love On The Run" is still quite enjoyable). But "Stolen Kisses" hits a spot, which films seem to never hit. It captures an age of awkwardness that seems to be ignored...the early twenties. Not like a typical high school or after college film (ie: "Risky Business" or "Graduate"), "Stolen Kisses" is about learning the survival skills to make it to adulthood (whether it's keeping a job, or making it in love). Antoine Doinel is in the third cycle of the series ("400 Blows" and "Love At Twenty/ Antoine And Collette" being it's predecessor), and Antoine has just been dishonourably discharged from the army for being of unstable character. Antoine haphazzardly begins to go through jobs, trying to find his nitch in life, while being obsessed with love. He begins as a nightwatchman of a hotel, to being a private detective of Blady's, which puts him as a planted spy in Monsieur Tobard's Shoe Shop, and finally settling down as an accident prone TV Repair man. Antoine is the awkward anti-hero youth of the sixties. During the 68' Paris riots (which were unbelievably carrying on during the filming), the youth of France had a sort of displaced position in the work force. Antoine (superbly played by Jean-Pierre Leaud) typlifies this kind of youth. He is full of nervous energy, politically working class, is love lorn, and uneducated. He is full of human qualities that are real and relateable. He lies, he loves, he fails, and he succeeds. He is just as much as the "everyman" of France, as Jimmy Stewart was in America. But interestingly, where he has once resembled director Francois Truffaut in the earlier works, he now was metamorphasising into Jean-Pierre Leaud's character, but resembling Truffaut more in look. Antoine Doinel was never meant to be just Truffaut, but Leaud as well. And the confusion of this identity is brilliantly displayed as Antoine confirms his identity by manically reciting his name in a mirror, displaying his search for identity to the point of near madness. The beautiful Clade Jade gives an underated performance as the hip, bourgoise student, that makes Antoine's obsessiveness seem somehow justified. The girl that is loved best by Antoine, when out of reach. The film also has a theme, about the differing strengths of love. When Antoine is in love with Christine, she doesn't love him. When Antoine loves Fabienne (the shoe shop's owner's wife), Christine is in love with Antoine. Every character is immersed in a love triangle. And asks the question, "Does love really ever exist on an equal basis?" But aside from the romantic cynicism, also lays some of the most romantic cinematic moments in history. The scene in which we follow up the stairs to find Antoine and Christine laying in bed peacefully, and the morning after, where Antoine purposes to Christne (with what looks like a fancy spoon or bottle opener, taking the place of a real ring?) is one of the most poetic moments in film history. The music score is fantastic as well as the cinematography gentle and sweet. For some, the ending is somewhat confusing and abrupt. But only shows, that the man that now stalks Christine with such passion, is now looked at by Antoine as resembling his once passionate feelings for her, that no longer burn with the same intensity. A bittersweet opening to the followup "Bed And Board," this film is a classic on all accounts.

No comments:

Post a Comment